LATEST UPDATES

Menu

There are many contributing factors to the justice gap, including a declining public investment in civil legal aid and the complexity of court process and procedure.

But scholars generally agree that a significant reason for the persistent and yawning justice gap is that states have long limited who can provide legal services.

In particular, lawyer regulations impose hefty entry requirements and pervasive constraints on practice. Taken together, these restrictions raise the price of legal services well above most Americans’ ability to pay. Even lawyers fresh out of law school frequently charge more than $300 per hour.

There are two main restrictions to consider:

If we changed these restrictions to allow more forms of legal services delivery to develop–new models for producing and delivering legal services–we should see increasing innovation, decreasing costs, and increasing access.

Every state has unauthorized practice of law (UPL) rules. In most states, these rules make it a crime for a non-lawyer to provide legal advice. In California, for example, a non-lawyer who furnishes legal advice can face penalties of a $1000 fine or up to one year in county jail, or both.

These rules have teeth because “legal advice” tends to be very broadly defined. It’s not just filing a pleading or appearing in court. In many states, in fact, the provision of legal advice refers to any application of legal knowledge to a particular circumstance. This broad ban has a wide reaching effect, effectively forcing people to choose between an expensive lawyer or nothing at all. Its enforcement, often at the request of other lawyers, prevents the emergence of alternative legal providers at lower price points. It even prevents people from offering free legal advice to those in dire need of help.

Domestic violence is a pervasive problem in our country. Survivors of domestic violence usually navigate the legal system alone as they seek assistance in the form of restraining orders, protective orders, or injunctions. Although most states allow lay advocates to support survivors, they are limited to providing only general legal information. They cannot give the survivor any legal advice or substantive assistance. This means that if the survivor is unsure of what facts she should include on her petition, for example, the lay advocate is not allowed to help. This may mean that the petition is incomplete and lacking relevant information, with serious negative consequences for the survivor.

The rules also undermine lawyers who want to drive innovation to serve more people, better, at a lower cost. Rule 5.4 of the Professional Rules of Conduct bans lawyers from sharing fees with nonlawyers under almost any circumstance.

This means that lawyers cannot take on outside investment or offer equity incentives to other professional experts, such as designers, technologists, or marketing experts. Lawyers also cannot work as salaried employees of corporations offering legal services to the public.

Ultimately, this rule means that lawyers alone must bear all the cost and all the risk of developing new ways to serve consumers. This has a particular impact on lawyers who want to harness technology to deliver “one to many” service models, where an individual lawyer’s expertise can be shared with many consumers at once, often by harnessing technology. Building such models requires technical know-how and financial capital that most lawyers lack. Lawyers could benefit by joining forces with technologists and tapping capital from outside sources.

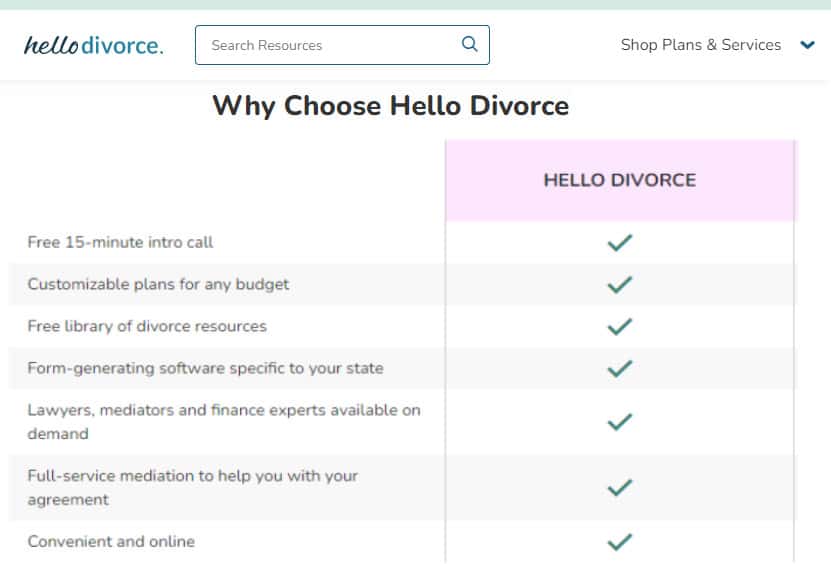

Erin Levine is a Bay Area family lawyer who realized she could use technology to help more people get affordable assistance. But, to do so, she has had to jump through unnecessary and costly hoops.

Because law firms can’t have non-lawyer investors, she had to set up a separate entity (Hello Divorce) to build her tech platform. And still, she can’t charge a flat, affordable fee for clients to access both “Hello Divorce” and get personalized help from a lawyer because that would be impermissible fee sharing between lawyers and others.

She calls regulation her biggest challenge in scaling her services to reach more consumers.